Making It real

My story in attempting to bring a new housing type that improves affordability, livability & community resilience

|

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) I apologies in advance that this article is quite broad; however, it reflects the extent and complexity in how the building code applies to built form. In this article, I will attempt to:

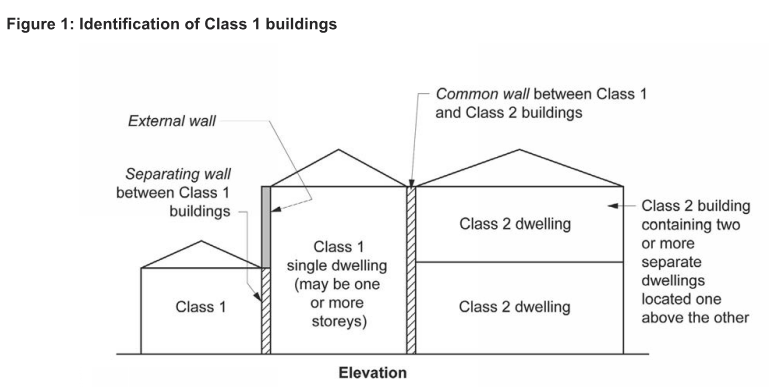

There are effectively ten (10) classes of buildings, of which two (2) specifically relate to residential living, Class 1 and Class 2. (there are subsets within these which I will explain later). Class 1 is your typical home that has some minor fire and acoustic requirements which is dependent on how close it sits from the site boundary. A class 2 building is generally your apartment building where the restrictions on fire and acoustic requirement's, amongst other items, are much more restrictive to protect the assumed increased number of occupants ("sole occupants") within the proposed building. The differences between building a class 1 versus a Class 2 are significant, not to mention the added planning requirements a Class 2 triggers. The fundamental rule that determines if a dwelling is a class 2 building is simply if a "sole occupant unit" exists above another. And this is when it starts to get a bit tricky, particularly if you partake in the sharing economy with the likes of Airbnb. Under the building code, if "a room or other part of a building is used for occupation by one or joint owner, lessee, tenant, or other occupier to the exclusion of any other owner, lessee, tenant, or other occupier" then it is considered that there is more than one sole unit in the building. In other words, if another person or persons can occupy and sustain themselves within another part of your dwelling without needing to be in contact with you, it is considered a separate unit and opens the risk of council penalising you or triggering sub-division requirements. So in some cases, leasing out rooms via Airbnb could be regarded as illegal. Extending upon this example, if both "sole units" are located on the same level, then you will need a fire and acoustic wall that separates them (see the two different Class 1 buildings in the diagram below). This arrangement is still classified as a class 1 building and is how most multigenerational homes work (see the five characteristics in the previous article). If, however one of these "sole units" is above the other, regardless of the house is just two levels, it becomes a class 2 building which triggers a whole raft of requirements which typically makes it unviable as a multigenerational home, hence why they don’t usually exist. When you place this in the context of a 2-story home with 4-5 bedrooms in a typical street, this is when it starts becoming nonsensical  Much of the building codes revolve around the protection of the residents within the proposed new building from external factors. As a class 2 building assumes that there are more people within it, it applies an increased risk profile and typically raises the requirements indiscriminately whether the building has 2 or 8 levels. In other words, the code has a preference to protect the inhabitants of the proposed new building from dangers created by a neighbouring building, not the other way around. A clear example of this is how the code deals with fire risk from a site boundary and how far the external treated face of the wall of the proposed new building needs to be from the site boundary. Unlike class 1 where it recommends you be at least 0.9m from the site boundary, Class 2 suggests a 3m setback, and if this is not possible, you will need to substantially increase the fire integrity of the wall which may even require the introduction of sprinklers. The additional requirements apply regardless whether the maximum number of inhabitants within a class 1 or 2 building are the same, which outlines the first nonsensical point. Non-sensical restriction number 1 As the number of residents in a 2 levelled, 4-5 bedroom home would be the same regardless whether classified as class 1 or class 2, the code still assumes that if it had a kitchen on the second floor (now under the rules considered as sole occupancy unit), it for some reason increases the risk of fire from the neighbouring building and therefore requires an increase in the external wall fire rating, amongst other things. Here is another way of looking at it. Below it shows you two different examples where the house type is the same expect one has the 2 kitchens and different aged family members. How does the building code view the fire risk? Amazingly it thinks that the the fire risk is now greater from the neighbour which doesn't have the 2nd kitchen, not that a 2nd kitchen should make much of a difference in the first case. Before I arrive on the second nonsensical restriction, it is essential to expand on the relevance of how we efficiently use resources (land) and why a 2nd kitchen on the second level is vital for a multigenerational home. It all starts with the broader need to make better use of space as land supply in our large cities is increasingly becoming restricted. As the amount of land is changing, our planning rules, unfortunately, are not. The constraining of land is resulting in the delivery of smaller homes with not only decreased backyards but also delivers poor accessibility outcomes for the elderly or disabled. (In Article 8 I described why I avoided splitting my design into two townhouses for this very reason). Density is forcing us to build up, and narrower buildings, yet in contradiction to this is the shift in urban household structures where families are staying together for longer. Even with the significant advantages that cohabitation brings, its success is very much dependent on the way we design the spaces within these homes to provide residents with the opportunities of having some degree of sanctuary and independence. An essential approach to achieving this is to provide different adult family cohorts with spaces that they: have control over; can retreat to, and can share with their external networks. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that cohabitation homes contain an element of flexibility for the possibility of having an additional living room and kitchen. Two living quarters does not mean that family households will never share a kitchen or eat together; instead, it merely provides the option to decide when or when not to. As we consider the challenges of density, there will increasingly be a consideration of incorporating a 2nd kitchen on the second floor of our homes as is common in other parts of the world. It is this arrangement which causes such uncertainty and concern within building controls which effectively results in it never occurring. Let me explain this further by using the example of a 2-kitchen home where the kitchens are on different levels within a 2-story house. The Building code deems that regardless whether the members in a household are related to one another; they are considered as sole occupants "if" they chose to live independent from one another for any period, be that one day or ten years. For this reason, it is often conservatively concluded that this house should, therefore requires assessment as a Class 2 building. It, therefore, must comply with more stringent fire escape requirements, even if the house may be the same size or have the same number of inhabitants as a class 1 building. The additional fire escape requirements can include such things as a further staircase and alternative fire-protected corridors amongst other things. This brings me to the second nonsensical restriction that would apply to a 2-story multigenerational house that had two kitchens. Non-sensical restriction number 2 - If all the items listed below were equal in two homes, other than one had a 2nd kitchen on the second floor,

then the one with the 2nd kitchen would require one or all the following BCA Class 2 requirements:

It is not overly explicit as to why a second kitchen or a second group of occupants (be they related or other) within a 2-story home would significantly increase the risk profile that would justify the extent of protection that a class 2 requires. The only plausible reason I have come up with is that if there was a fire caused by an occupant on one floor, there might be some concern in the delay it takes for the other occupant on the different floor to be alerted of the imminent danger. Notwithstanding that this is easily solvable by simply installing connected smoke/heat sensors throughout the house, the risk profile of the Multigenerational house should be seen no differently to a typical two-story family home (class 1) where all bedrooms are located on the top floor. Finally, the other potential cause of concern of a 2nd kitchen on the second floor is its ability to create a flame. This risk is again easily manageable by merely ensuring the stove is electric rather than gas. I should highlight here that I rang the Australian building code of Australia to question them on how they determined risk. They were unable to provide me with a reason but what was amazingly was that they informed me that they “NEVER” provide advice in writing. I’ll let you decide if that is an appropriate response from a national governing body.

In summary, the building code illogically treats a multigenerational home with two kitchens as a more significant threat than a standard residential dwelling of the same size. There are only a few changes to the code that would remove this impost; however, this is not possible without also considering and amending the local planning scheme. Before expanding on the planning in the next article, it’s important to highlight that there are two Class 1 building types; Class 1a and Class 1b. Your typical family home, which I have referred to so far in this paper, is known within the code as a Class 1a building. The alternative Class 1b is very similar and is treated much in the same way. Its main difference is that it is more like a boarding/rooming house that has up to 9 bedrooms but less car park requirements. For ease of reference, where I refer to Class 1 in this article, this has been used to describe a class 1a type building, however, in the next article I specifically relate to Class 1b as it is very relevant to the finding a solution to the issues I am seeking to address in this quest.

1 Comment

|

Over 25 years experience in both the private and public sectors o f property

A lover of technology and design that is practical, beautiful and improves the way we live not as a individuals but as a thriving community. Archives

January 2021

Categories |