Making It real

My story in attempting to bring a new housing type that improves affordability, livability & community resilience

|

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) When starting this, I never knew that I would have had to travel such a journey. Would I have started this knowing that there was such illogical and incomprehensible resistance to a solution that could benefit so many? Absolutely. If anything, as a result of being forced to traverse down the many rabbit warrens, it has only strengthened my resolve as I am much more confident of the roadblocks than I ever have been. And they are not insurmountable. I can’t help but feel that it is somewhat a shame that the authorities we rely on to solve planning and housing issues are part of the cause as to why the problems exist in the first instance. Yet the authorities have so much to deal with that sometimes they too can become overwhelmed by the multiple responsibilities they have to deal with and maybe sometimes, it also needs others to challenge what they do and provide alternative approaches. In saying all that, there is not a great deal that needs to change in allowing more multigenerational homes, yet there is a need for change. The suggested amendments to current planning and building rules are outlined below. If these amendments are adopted, then in the long term this slight change should provide more opportunities for families to take better care of their aging parents, children or disabled family members while also improving our broader approach to sustainability, housing affordability and community resilience. A multigenerational house should:

If these rules are implemented, then we will be making it real. The journey, however, does not stop until the prototype is built to demonstrate what such a house the meets these rules, looks and feels and behaves (Image above). In the next few articles, I will explain the planning strategy taken, how the home design embraces flexibility allowing to have multiple configurations, the building approval process and hopefully the fun part where I can start adding photos of the thing coming out of the ground! The one thing that I haven’t highlighted here is that the final confrontation with the authorities will occur when the house is built. At this stage, it will not yet be a Multigenerational home; however they will be given a chance to determine if it can be. If you want to hear how this works out, please register for updates.

0 Comments

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) In my previous article, I described how restrictive and illogical the Australian Building code was when confronted with a multigenerational home that had two kitchens. In this article, I will outline how the planning system can influence the building code while providing yet another nonsensical scenario that the current rules create which surprisingly seems to be supported by both the building and planning authorities. First, let's look at an example where planning has influenced a build form outcome. Before we start, have a look at the images below and ask yourself, which would you think posses the greater fire risk? A planning scheme can guide the building code as it has with Rooming Homes. Under the building code, a rooming home is considered very similar to a typical residential home bar a few minor differences. Both attract class 1 classifications with a standard residential home being a Class 1a, while a rooming home is a Class 1b. The critical difference is that a Rooming house identifies as a housing specific for the accommodation of disadvantaged people. Other than this, there are many similarities between it and a multigenerational home. To highlight this, let’s review how both the planning scheme and building code approach this type of class 1 building. Under clause 52.23 of the Victorian planning scheme, it outlines the critical criteria needed for a home to qualify as a Rooming house. In parallel to this, the building Code has specially developed a building type, Class 1b, that aligns with the planning restrictions which state that dwelling should not:

Even though very similar to class 1a, there are some minor differences; The Building code identifies that the facilities are designed to be shared and that there must be a full DDA compliant bathroom and car park. It also requires increased fire escaping measures that are far less stringent than what a Class 2 building would need (refer to article 12). This high level of amenity in a rooming house is designed to protect disadvantaged people of our society, who generally are not related to one another. This now brings me to nonsensical restriction number 3. Non-sensical restriction number 3 Which would you consider attracts the higher fire risk? A) A 2-storey multigenerational home with 4-5 bedrooms, two kitchens and residents that are generally related to one another; or, B) a 9-bedroom dwelling with disadvantaged strangers. According to the Build Code, it is A) Yes, the Multi-Gen house unbelievably is assumed to posses the greatest fire risk.... Notwithstanding the above and the fact that both the building codes and planning scheme are silent on the ability to have a second kitchen for a rooming house (class1b), this building class, subject to a few adjustments, could provide the right solution in increasing the supply of more multigenerational homes. So, what would these amendments be? I will outline this in the next article.

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) I apologies in advance that this article is quite broad; however, it reflects the extent and complexity in how the building code applies to built form. In this article, I will attempt to:

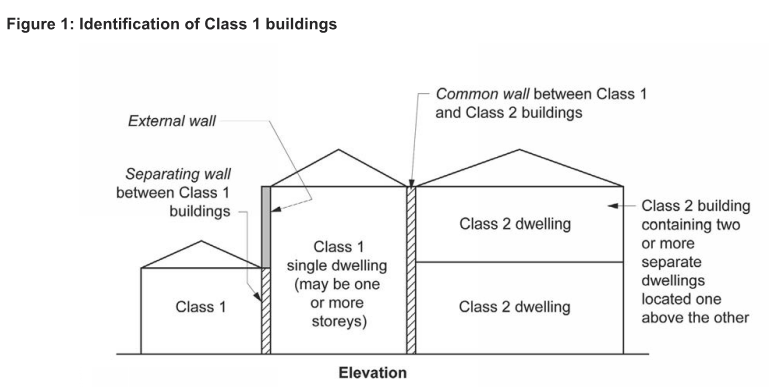

There are effectively ten (10) classes of buildings, of which two (2) specifically relate to residential living, Class 1 and Class 2. (there are subsets within these which I will explain later). Class 1 is your typical home that has some minor fire and acoustic requirements which is dependent on how close it sits from the site boundary. A class 2 building is generally your apartment building where the restrictions on fire and acoustic requirement's, amongst other items, are much more restrictive to protect the assumed increased number of occupants ("sole occupants") within the proposed building. The differences between building a class 1 versus a Class 2 are significant, not to mention the added planning requirements a Class 2 triggers. The fundamental rule that determines if a dwelling is a class 2 building is simply if a "sole occupant unit" exists above another. And this is when it starts to get a bit tricky, particularly if you partake in the sharing economy with the likes of Airbnb. Under the building code, if "a room or other part of a building is used for occupation by one or joint owner, lessee, tenant, or other occupier to the exclusion of any other owner, lessee, tenant, or other occupier" then it is considered that there is more than one sole unit in the building. In other words, if another person or persons can occupy and sustain themselves within another part of your dwelling without needing to be in contact with you, it is considered a separate unit and opens the risk of council penalising you or triggering sub-division requirements. So in some cases, leasing out rooms via Airbnb could be regarded as illegal. Extending upon this example, if both "sole units" are located on the same level, then you will need a fire and acoustic wall that separates them (see the two different Class 1 buildings in the diagram below). This arrangement is still classified as a class 1 building and is how most multigenerational homes work (see the five characteristics in the previous article). If, however one of these "sole units" is above the other, regardless of the house is just two levels, it becomes a class 2 building which triggers a whole raft of requirements which typically makes it unviable as a multigenerational home, hence why they don’t usually exist. When you place this in the context of a 2-story home with 4-5 bedrooms in a typical street, this is when it starts becoming nonsensical  Much of the building codes revolve around the protection of the residents within the proposed new building from external factors. As a class 2 building assumes that there are more people within it, it applies an increased risk profile and typically raises the requirements indiscriminately whether the building has 2 or 8 levels. In other words, the code has a preference to protect the inhabitants of the proposed new building from dangers created by a neighbouring building, not the other way around. A clear example of this is how the code deals with fire risk from a site boundary and how far the external treated face of the wall of the proposed new building needs to be from the site boundary. Unlike class 1 where it recommends you be at least 0.9m from the site boundary, Class 2 suggests a 3m setback, and if this is not possible, you will need to substantially increase the fire integrity of the wall which may even require the introduction of sprinklers. The additional requirements apply regardless whether the maximum number of inhabitants within a class 1 or 2 building are the same, which outlines the first nonsensical point. Non-sensical restriction number 1 As the number of residents in a 2 levelled, 4-5 bedroom home would be the same regardless whether classified as class 1 or class 2, the code still assumes that if it had a kitchen on the second floor (now under the rules considered as sole occupancy unit), it for some reason increases the risk of fire from the neighbouring building and therefore requires an increase in the external wall fire rating, amongst other things. Here is another way of looking at it. Below it shows you two different examples where the house type is the same expect one has the 2 kitchens and different aged family members. How does the building code view the fire risk? Amazingly it thinks that the the fire risk is now greater from the neighbour which doesn't have the 2nd kitchen, not that a 2nd kitchen should make much of a difference in the first case. Before I arrive on the second nonsensical restriction, it is essential to expand on the relevance of how we efficiently use resources (land) and why a 2nd kitchen on the second level is vital for a multigenerational home. It all starts with the broader need to make better use of space as land supply in our large cities is increasingly becoming restricted. As the amount of land is changing, our planning rules, unfortunately, are not. The constraining of land is resulting in the delivery of smaller homes with not only decreased backyards but also delivers poor accessibility outcomes for the elderly or disabled. (In Article 8 I described why I avoided splitting my design into two townhouses for this very reason). Density is forcing us to build up, and narrower buildings, yet in contradiction to this is the shift in urban household structures where families are staying together for longer. Even with the significant advantages that cohabitation brings, its success is very much dependent on the way we design the spaces within these homes to provide residents with the opportunities of having some degree of sanctuary and independence. An essential approach to achieving this is to provide different adult family cohorts with spaces that they: have control over; can retreat to, and can share with their external networks. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that cohabitation homes contain an element of flexibility for the possibility of having an additional living room and kitchen. Two living quarters does not mean that family households will never share a kitchen or eat together; instead, it merely provides the option to decide when or when not to. As we consider the challenges of density, there will increasingly be a consideration of incorporating a 2nd kitchen on the second floor of our homes as is common in other parts of the world. It is this arrangement which causes such uncertainty and concern within building controls which effectively results in it never occurring. Let me explain this further by using the example of a 2-kitchen home where the kitchens are on different levels within a 2-story house. The Building code deems that regardless whether the members in a household are related to one another; they are considered as sole occupants "if" they chose to live independent from one another for any period, be that one day or ten years. For this reason, it is often conservatively concluded that this house should, therefore requires assessment as a Class 2 building. It, therefore, must comply with more stringent fire escape requirements, even if the house may be the same size or have the same number of inhabitants as a class 1 building. The additional fire escape requirements can include such things as a further staircase and alternative fire-protected corridors amongst other things. This brings me to the second nonsensical restriction that would apply to a 2-story multigenerational house that had two kitchens. Non-sensical restriction number 2 - If all the items listed below were equal in two homes, other than one had a 2nd kitchen on the second floor,

then the one with the 2nd kitchen would require one or all the following BCA Class 2 requirements:

It is not overly explicit as to why a second kitchen or a second group of occupants (be they related or other) within a 2-story home would significantly increase the risk profile that would justify the extent of protection that a class 2 requires. The only plausible reason I have come up with is that if there was a fire caused by an occupant on one floor, there might be some concern in the delay it takes for the other occupant on the different floor to be alerted of the imminent danger. Notwithstanding that this is easily solvable by simply installing connected smoke/heat sensors throughout the house, the risk profile of the Multigenerational house should be seen no differently to a typical two-story family home (class 1) where all bedrooms are located on the top floor. Finally, the other potential cause of concern of a 2nd kitchen on the second floor is its ability to create a flame. This risk is again easily manageable by merely ensuring the stove is electric rather than gas. I should highlight here that I rang the Australian building code of Australia to question them on how they determined risk. They were unable to provide me with a reason but what was amazingly was that they informed me that they “NEVER” provide advice in writing. I’ll let you decide if that is an appropriate response from a national governing body.

In summary, the building code illogically treats a multigenerational home with two kitchens as a more significant threat than a standard residential dwelling of the same size. There are only a few changes to the code that would remove this impost; however, this is not possible without also considering and amending the local planning scheme. Before expanding on the planning in the next article, it’s important to highlight that there are two Class 1 building types; Class 1a and Class 1b. Your typical family home, which I have referred to so far in this paper, is known within the code as a Class 1a building. The alternative Class 1b is very similar and is treated much in the same way. Its main difference is that it is more like a boarding/rooming house that has up to 9 bedrooms but less car park requirements. For ease of reference, where I refer to Class 1 in this article, this has been used to describe a class 1a type building, however, in the next article I specifically relate to Class 1b as it is very relevant to the finding a solution to the issues I am seeking to address in this quest. (Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) It’s common to receive a surprising response when I mention to people that there are significant restrictions in building multigenerational homes within the suburbs of Australian cities. That is not to say multigenerational households don’t exist, as an internet search will prove. What is challenging to extract from this search and to explain to people are the five prominent key characteristics that exist in most of the examples that one can find. Unbeknown to many, these characteristics are typically a consequence of the planning and building rules and do not necessarily present the best outcome that would otherwise be possible. Even though the existing examples demonstrate multigenerational homes are achievable, its more the exception than the rule. Hopefully, by outlining the key characteristics, as listed below, it will start to highlight why a multigenerational home with two kitchens over two floors is not possible. Examples of multiGen homes The 5 Key characteristics often found in Multigenerational homes:

Image below- The loss of private useable backyard space in subdivided lots Consider how much the shared driveway wastes private space. The green shaded areas represent valuable private open space for each dwelling. Which would be more useful to a growing family? It’s the last point (the kitchen) that raises the biggest challenge for authorities. Even though some homes have a second kitchen for religious reasons, these are only accepted because they are typically adjoining the central kitchen. It’s when kitchens are located within the same home that allows different groups to prepare meals in isolation from one another that creates anxiety for Planning and Building authorises. As absurd as this sounds, but this is the key sticking point in allowing a modest-sized multigenerational home existing within a typical suburban setting. In otherworld’s, a 2-story home with a kitchen on either floor is discouraged by the existing rules. It is not as though Planners or Building Surveyors are not wanting to promote this home type; it’s more a consequence of the rules set by Planning and building Authorities who are either unwilling or are simply out of touch with the changing household demographic profiles of modern Australian families. The whole purpose of all these blogs is to raise awareness that the authorities, intentionally or not, are themselves the problem and from the communications, I have had with them; this will not change anytime soon. Of these two authorities, the Australian Building Code Board (ABCB) is the most restrictive and perhaps the more complex. In the next article, I will outline the basic principles of the building code that is specific to residential living and how they apply to the urban context we have within Australians cities. I will then highlight two of the three rulings that nonsensically restrict an increase in the supply of multigenerational homes within most of our metropolitan landscape. Click on the image below to go straight to the article

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) Make sure you spend your time getting the right building surveyor. The control and influence they can have on your project are like having someone in your bed until your house keys are handed over. The realisation that I could be stuck with a very unhelpful and unresponsive surveyor are the moments that create sleepless nights. Unlike other consultants, the building survey once engaged, needs to register the project with the building commission. It’s like a short-term marriage. This arrangement is to prevent unscrupulous builders from replacing law-abiding surveyors with another more “flexible” surveyor how might show a blind eye to poor workmanship. For this reason, the building commission requires justification from you as to why you wish to remove a project registered building surveyor. This process is made much more complicated if the surveyor does not agree with the removal, meaning it could drag out the building process for months. For this reason, the power that building surveyors have on projects is dangerously high meaning that if you have an antagonistic relationship with this consultant, you can be in a world of pain. Luckily for me, my original building surveyor, after providing their initial advice and collecting “all” their fees, agreed to remove themselves from the project and the process went smoothly. However, this was not the end of the challenges that revolved around the building surveyor and the extent it would impact me was severe. What was it exactly that brought all these complications to the surface? Naturally, the fact I just wanted to install a 2nd kitchen. (I suggest you read the article below) When communicating with drawings to my original building surveyor what I wanted to do, they were only too happy to assist and as quick as kids opening Christmas presents, they issued me an agreement that registered their role with the building commission. After the initial review of the house, variations came quickly for additional “unforeseen” reviews of which none provided clear guidance on the fundamental idea of the design, the second kitchen. Around the time I replaced the architect, the building surveyor was increasingly becoming nonresponsive and would only drip-feed information, frustrating both the new designers and me. It was at this point I discussed my concern with the surveyor and discovered that the second kitchen was complicating matters beyond their willingness to assist. It was incredibly disappointing as this design concept was discussed at length before engagement occurred. I had effectively paid a consultant that was never going to provide me with the service that I had requested at the onset. I perhaps had cause not to pay my fees, however knowing I could be tied up at the commission for an excessive period, sometimes it's best to cut your losses and move on. Being let down once more, I persisted and thanks to Mesh Design I landed on a new building surveyor relatively quickly. It wasn’t long before I became increasingly aware of just how complicated the world of the building surveyor was. Building surveyors have the responsibility of being the protector and policeman of good building quality. For this reason, they often get abused or challenged by builders who have an interest in cutting corners or are seeking a “deem to comply*” solution. (* When the rules allow some level of interpretation, and as long as the design outcome delivers on the intent of the law, the building surveyor has the authority to approve an alternative approach). Even though they have a significant influence on a project, a building surveyor has the too often yet unfortunate task of outlining why aspects of designs are not achievable. As the laws discourage them in providing specific design guidance in how non-compliant designs are resolvable, it can become an inefficient process of going back and forth in the hope that the resubmitted design will gain the required marks to pass, if at all. The building surveyor's role is complicated when you consider the extensiveness of the building codes (There are 3 volumes and a guide book on average about 600 pages long!) and how it often also needs to be found in light of the local planning policy which can also be up to 600’s pages. It was becoming more apparent just how excessively complicated it was to obtain a permit and if you were to attempt something the building code or planning had not taken into account, God help you! I was discovering that the journey I was embarking on was just about to take a turn for the worse. Without going into too specific building and planning rules here (See future articles), the core issue for the building surveyor in supplying me with what should have been a straight forward building permit was that the proposed second yet flexibly designed kitchen (it could be installed or hidden depending on what layout you needed) was on the 2nd level whilst the first one was on ground level. The Surveyor highlighted that this was the core item that created a conflict as to which “Class” they should classify the building which would then provide the necessary guidance as to how to asses it. As a result, he did not have the authority to approve the design and directed that I seek local council consent. Perhaps not a surprise to me so much now, but the outcome of the conversations with the council was some options as to what may assist me in my cause, but no clarity or certainty of approval if I choose to follow some of the costly options they suggested. Even though council seem to agree with the merits of what I was seeking to achieve, they were not comfortable in supplying approval of the house design with two kitchens and suggesting that it was more a Building code issue. (refer to my future comment from the National Building code Authority on this statement) As a result, I was forced to remove the second kitchen from the set of drawings in a bid to obtain councils consent on several other, less controversial design matters. As the kitchen was however fundamental to the ultimate design, I was forced to reconsider an alternative approach in how I could influence both the planning and building authority to become more an enabler than an impediment to the delivery of multigenerational homes. So began my journey into the multimedia space and world of webs designs, blogging and animation production.

The explanation of the relationship between planning rules and the building code is quite a complicated one, so I have broken this into four separate articles. In the first, I will respond to the common question I get from people where they are bewildered by my quest, believing there are already multigenerational homes or houses that have two kitchens. The second article will explain how the building codes apply to residential housing, and I will outline 2 of the three nonsensical outcomes these rules create. In the third, I will expand on how the planning system influences building code outcomes and contributes to the third nonsensical outcome from the regulations it enforces. Finally, I will close out with a suggested solution in how these rules could easily be amended to convert the authorities from being inhibitors to becoming enablers in the supply of multigenerational homes. Hopefully, by now, I haven’t tired you out as the next three will take some effort to get through as they are quite technical. (Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) To know all is to rid the world of mystery and what is a world where magic no longer exists. Mystery is where I placed my hope to soften the disappointment I was feeling from my early Archbazar submissions (Refer to the last article). The designers are free to submit their designs any time before the deadline and as the more came in, the less inspired I became. The first one was interesting, the next one outrageous, and the remainder made me wonder whether someone was taking the mickey or whether they thought middle-aged white male in Australia were overweight and loved palm trees. Refer to the 70’s Miami hotel-inspired image below. As the somewhat uninspired designs were submitted well before the deadline, I still harboured hope that I would still receive something of value. This hope quickly dissipated as the deadline increasingly became nearer. I was contemplating the reality that this might be a disaster and I was going to have to return to the original uninspiring design. Then I received a late request to extend the deadline from a detailed questioning designer. Considering the submissions, I had received to date looked as though high school students designed them, I had no other choice to extend the deadline. To their credit, the website agreed without too much fuss and then I waited another ten days to contemplate what my plan B would be if the later submissions were no better than those previously submitted. After having my head in my hands, I quickly raised my arms in celebration after receiving the final submission on the last day! Even though I received some exciting designs, (Refer to the tree house above), only one of the designers considered the orientation of the sun. I still find this incredibly surprising that this is still not the primary question designers ask first. It was therefore not surprising that the person who would eventually win was the only designer from the southern hemisphere, South Africa. Not only did he design to suit solar conditions, but he was the only person who addressed the design challenge. He came up with a creative approach to redesigning the front stairwell, which not only functioned better, but it created a much more interesting external form. I instantly fell in love with this design solution and finally felt validated for that leap of faith to explore and invest in an alternative design platform. Unfortaulety, this emotion was not shared by my Architect. Many architects are known as having a somewhat sensitive and protective reputation when it comes to their design style. Some treat their design output as an extension of themselves and purposefully leverage this as their unique brand and IP. Afraid of not being distinguishable from other designs, some may work in isolation or possibly restrict others from influencing their design. Yet in a world hungry for design thinking to solve current issues, there is a need to collaborate & share knowledge. It is almost archaic for designers only to participate where they are the sole player. The rules of creativity as a commodity are evolving, and opensource platforms such as archabazar are redefining the value of design, but more importantly, how we act as participants. In my case, my architect provided me with an ultimatum; if I pursued the design outcome which I fell in love with, he was no longer willing to contribute. So, that began my search for another design consultant.

Not wanting to be faced with the prospect of professional sensitives, I sourced out a building designer who would take me through to tender drawings. I hooked up with Mesh design which has been fantastic. What was quite surprising is just how many errors and rework was required to amend the work by the previously registered architect. The lessons were building up. Nonetheless, I thought I now had a clear path, and building commencement was just around the corner. The year was 2016. It wasn’t long before I would hit yet another roadblock and I would yet again face the need to remove another consultant, but this time it was the building surveyor. However, this removal not only highlighted the variability in consultancy services one can experience, but it also uncovered a broader issue. The challenge was only going to get tougher as I was soon to become aware that I would have to convince the planning authorities of a different approach and challenge the building code itself. (Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) From the onset of this journey, I wanted to find a solution that not only made it easier for people to own a home but would hopefully improve their lives beyond the basic concept of a roof. In considering the complexity surrounding housing, I knew that traditional mechanisms or ideas would not suffice and I would need to explore technological advancements and alternative approaches in how we might design and construct a home. Innovation was always going to be at the core of this journey, but I never thought it would lead to four distinct areas. They were to:

The highly recognised urban studies theorist, Richard Florida, is known for his description of a cohort that he predicted would surpass the traditional demographic profiles of blue and white colour. He coined this new breed of the urban dweller, the creative class; A group who were primed to think differently and would design a new path for society. Much of this would evolve from Silicon Valley, where it led to the establishment of a binary fueled economy that has time and time again shown its potential to disrupt any industry. Its reach of disruption seemed only limited by imagination. Even though creativity would explode in all things digital, it would eventually be responsible for devaluing traditional skills in a blink of an eye. Think of travel agents, retailers and general administrators. Yet even though computers were not able to replicate human creatively or ingenuity, it did allow for crowdsourcing where the power of millions of minds was accessible at a fraction of the cost. Crowdsourcing platforms popped up all over the place, including in the protected sphere of design. Platforms like 99 designs and Archbazar were placing more control of creatively in the hands of the person in need of the inspiration, or in my case, the need for solving a problem. The internet had levelled the commodity of creatively, and I needed some inspiration. As touched on in the last article, I was ready for an alternative design approaches and would ask the world of designers through the Arcbazar website to help me find a design solution. So how does Archabazr work? Archbazar is simply a platform that has preregistered designers from around the world with varying degrees of skills and expertise. You establish a design competition by supplying a brief of what you are after with any supporting information that you believe the designers need to understand the context of your challenge. You set the timeframe and the prize money eventual is distributed to the three best submissions which are determined by you. The first place attracts 70% of the price money, second 20% and 3 rd 10%. If your needing support to decide which deserves the first prize, you can invite friends and family to rate submission and provide commentary. The quality of the information received typically depends on the prizemoney you set. However, the examples I had reviewed before deciding to go down this path demonstrated the design output easily surpassed the prize money required. The examples supplied in this blog show some of the quality from the submissions received; however, the images alone do not do the website justice as to how much designer material each submitter supplies. It’s simply unbelievable to what length some designers go to. The only way to discover what is possible is to check the website for yourself. After researching several crowdsourcing design options, I was satisfied that Archbazar suited me best and signed up. I then proceeded to write the brief, attached the necessary documents and after paying my prize money, I sat back with a surprising sense of excitement and anticipation. It wasn’t long before I received notification that a designer from Romania, Thailand, India and California had reviewed or downloaded my pack of documents. Even though I had no idea if they would submit, the simple knowledge of them just looking at it was like a dopamine hit probably akin to receiving news that tomorrow will be 23 degrees and sunny. (That means a lot when you live in Melbourne, and it’s the middle of August). The website provides a world atlas where it places a pin on the location from where the interested designer was from and this only increased the mystery as to who was this person that I have indirectly invited into my world to help me out? This new form of global collaboration was unexpectedly exciting. But that was nothing like what I would feel when the submissions would come it, and boy was that a roller coaster. Why? Check out the next post.

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) So now I have a design in hand what now? At this stage, I was not across all the regulation and rules, so I needed to acquire some additional help. A consultant that I had previously worked with was embarking on a self-consultancy practice and was eager to undertake some residential work. The combination of him being a gentleman and I had design and construction experience had me asking the question, "What could go wrong?!” So, I engaged him. It wasn’t long before I soon realised that my growth spurt in learning through mistakes would never end. The practice of design has always fascinated me. The variables that are required to be considered, conjured and reimaged is an extraordinary process. Throw into it the need to have a general understanding of engineering, legal, finance and human behaviour, and you can start to grasp the beehive of activity that can often reside within a designer’s mind, in particular, that of an architect. Yet somewhere in the process, (so I am led to believe) their early teachings encouraged them to push back on clients ideas or directions that did not align with their own. Even though we worked through several items where collaboration produced some intelligent solutions, I was struggling with continuously being encouraged to embrace an external form that I did not relate to. After requesting different varieties, I struggled to fall in love with it as it would remind me of an 80’s shop. I thought it deserved more yet I was not getting the same love from my architect. Somewhat like any relationship, the collaboration process with the design fraternity can be an enriching experience where you’re both pushing and pulling ideas or problems as you all search for design solutions. Yet the journey together often starts haphazardly as discoveries are more likely to be problems and constraints rather than reflections of grand visions. An example of this for me was during what became a “napkin twisting” exercise of trying to meet the required boundary setbacks while seeking to respect the adjoining Victorian terrace. After countless attempts, I had hoped that the right design outcome would float to the surface, yet no matter the many iterations created, my internal design fire would not ignite. It was time to raise the prospect of an open relationship with a new design partner, Archbazar. Archbazar was at the time, a relatively new crowdsourcing architectural design platform. Its platform allowed Clients to log design competitions where any registered designer from around the world could submit a design and if successful, would claim a proportion of the prize money. My early exploration of design crowdsourcing lead me to this discovery, and the more I was becoming disillusioned by the plans I was receiving from my architect, the more I wondered if I could use this platform to find a solution or a unique design response to the challenge before me. I was becoming increasingly interested in giving this a go-to design the front of my building, so I asked my current designer if they were comfortable in an open design relationship with a broader audience. At first, he agreed…but as I suspect with many open relationships, it was doomed to end in tears. In the next article, I will explain the story of jumping in bed with Archbazar and what I received in exchange.

(Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles) I’m not sure if shared by others who have bought a “renovators Dream”, but a few hours after landing the home, a wave of shock hit as the gravity of what I signed up to started to become more apparent. I just bought a house that wasn't even livable nor looked structurally sound. I needed to act quickly so I could get renters in to help cover mortgage payments. Even though I didn't own a house at the time, I will admit I was a bit precious in that I didn’t think I could live in a house that was in such a poor condition. Yet I was soon to be proven wrong about its immediate “livability”!. Not soon after I took possession of the house, I arrived to start renovation works and found not only had someone changed the front door lock on me, but I had squatters living inside the house! A group ranging from 14 to 30 years old had not only taken residence but had looked as though they had had a pretty decent party the night before! After negotiating their departure over 2 hours, they slowly rolled out on bikes that could only be described as a collage of bike parts from different decades. With saddles hanging from the front, back and sides of these pieces of art, the scene was not unlike a caravan of explorers going in search for new lands (or homes) to conquer. What was also surprising was just how many there were considering it was a tiny house. It was like watching an army of circus clowns climbing out of a minicar, but instead of clown outfits, they were wearing a soup of steampunk-rainforest attire. I lost count, to be honest, but it was quite a spectacle watching this herd of bikes ride off around the corner. Yet that wasn’t the end of it. Not knowing what I would find in the house, I was shocked to find a considerable amount of house goods that they must have gathered over two days. It appeared they had plans that they were in for the long haul. This certainly wasn’t the type of excitement I had in mind when starting this journey, yet I would soon find out that this was just the beginning of the many twists and turns requiring constant problem solving and negotiating.  After completing the renovation works, which I enjoyed way too much, the house actually came-up a treat which made me wonder why I wasn’t moving in myself. I eventually found a tenant, giving myself some time to work on what my future home would look like. It was during this early design phase that I started to challenge how a house for life might function, which helped galvanise my belief on the benefits of a multigenerational home. There is something quite magical about the process of designing as you regularly test scenarios over and over in your mind as you work through how one might use a different configuration of spaces. The number of iterations was too numerous to count, but they seemed insignificant as I became fixated on trying to design a house that looked like any other from the street, but internally would allow two families to co-live with one another with a desired level of independence. However just like any creative process, particularly when trying to solve a problem, it can be a bit of roller coaster as you ride the waves from the thrills of reaching that “ah-ha” moment, only to quickly come crashing down once you discover how quickly regulation waters the flames of inspiration. Many lessons were learnt during the initial design phase, non-more so that the importance of the width of your land lot. This measurement is crucial when seeking to design for those with mobility issues, be it for ageing in place or those with a disability. I quickly found that typical townhouses wouldn't work on anything less than 10 meters. Legislative spatial requirements for mobility-impaired or large families demands significant space. This highlighted that if we continued on the current infill development trajectory of subdividing lots into typical townhouse developments, society would have a limited supply of new homes that meet ageing in place demands. (Hello Royal commission on aged care!) It was here where I challenged the notion, “if designing within the rules restricted the solution, then do the rules need changing?” Current media continually warns us that we are in an age of disruption, where the pace of change in the way we are living is forcing us to challenge existing rules. To meet this change, being flexible and adaptable are now considered crucial survival skills, yet we would be hard-pressed to find many examples where our typical house layouts demonstrate these traits. Yet I come to discover there was a reason why Flexibility isn't a more commonly used word in the context of house designs; it’s merely incredibly tricky. I came to this realisation as I worked through the many different family arrangements that could exist within one home and how I could address their needs so that they didn’t fill forced to move every 7-10 years. I went through so many designs, but I knew that Flexibility was to be the centre of what I wanted to design, and finally in 2011, I had that “A-HA" moment. Due to the restrictive size of the lot, approximately 350m2, the design process forced me to design two stairs with a second kitchen on the second floor. By designing the second kitchen to be easily dismantled and reinstated, the house could function like a single-family home which I was assuming would be its primary use. There were a few bugs that needed to be ironed out, but I was ready to find someone who could transport it to Architectural drawings and get it ready to build. I was prepared for the next stage; building my design team. (Please note that this article is one in a series and it may make references to previous articles)  For those who have been there, you know the pain of the hunt. For those that are yet to embark on it, don’t read on, it might prevent you from ever starting. Looking to buy property is a torturous process particularly when you’re not swimming in cash and going to open inspections at times felt like being at boxing day sales. Everyone is potentially an enemy who might take away your prize, and the worst comes out of you as you indiscreetly publicise every discovered fault in the hope it would discourage others or at best, suppress the price. The dislike for the process started at the front door. Each time you arrived, you would be welcomed by some swami, wet eared estate agent who barely knew more than the address they were standing on. I quickly came to despise this unhelpful profession as I was made to feel like a number as they barley lifted a finger. This was occurring in what was a golden time for property in one of Australians biggest property boom. It was 2009, and even though the Global Financial Crisis was soon to take centre stage, there was pressure to buy anything as house prices were seemingly rising weekly. It was like running a race; if you didn’t cross the line first, you were forced to do another lap. It was exhausting. The worst part? Was coming to realise the limited options my budget allowed. The realisation brought disappointment, sadness and anger all at once. It was a hard pill to swallow, but you didn’t have much time to ponder because the market was so hot, and you just needed to keep running to stay in the race. Even though starting in Northcote, I would spread my glance into Thornbury and then to Preston. Losing at auctions on the way I would constantly wonder about affordability and how anyone, in particular, young families would ever be able to afford anything in here. It was during this time that I was contemplating the value of a multi-generational house as I was looking for alternative affordable options. There had to be a solution through design, and I was adamant that it existed in a flexible house design which could adapt with its homeowner. After being recharged with this new design approach, I set some core criteria. The house needed to be in an irreparable state to justify its demolition, it needed to have a north-facing backyard, it needed to be within reach of a train line to reduce car dependency, and it needed to be facing a train line. The last point was a touch mad, but I had some logic behind it. Being along a train line not only meant it would attract a discount due to noise pollution, but it would also force me to learn more about acoustic engineering. Understanding acoustic attenuation would be important not just because I was seeking to design a house where two families could live independently of each other, it would increasingly become important as society increasingly lived closer to one another. We rarely give enough consideration of the impacts of sound; however, I was adamant that this would change over time.

With my new criteria, I watched the market like a hawk, and there I was, two days before Christmas bidding for a house that met the set criterion. As expected, there was only a small number of bidders, two to be exact, and before the end of the day, I was the proud owner of my modest piece of land with a house that had no kitchen and defied the rules of physics. Even though I was on this journey for some time, this was certainly a milestone. It was now to convert all my thinking and ideas into something tangible. It was now my time to make this real. |

Over 25 years experience in both the private and public sectors o f property

A lover of technology and design that is practical, beautiful and improves the way we live not as a individuals but as a thriving community. Archives

January 2021

Categories |